|

| Title page of Eureka first edition (Putnam, 1848) |

Discarding now the two equivocal terms, “gravitation” and “electricity,” let us adopt the more definite expressions, “Attraction” and “Repulsion.” The former is the body; the latter the soul: the one is the material; the other the spiritual, principle of the Universe. No other principles exist. All phænomena are referable to one, or to the other, or to both combined. So rigorously is this the case—so thoroughly demonstrable is it that Attraction and Repulsion are the sole properties through which we perceive the Universe—in other words, by which Matter is manifested to Mind—that, for all merely argumentative purposes, we are fully justified in assuming that Matter exists only as Attraction and Repulsion—that Attraction and Repulsion are matter. . . .Eureka has vexed readers and critics alike since its first publication. A contemporary review in the Literary World panned it as “arrant fudge” and “extraordinary nonsense, if not blasphemy,” and exactly 100 years later T. S. Eliot harrumphed that it “makes no deep impression . . . because we are aware of Poe’s lack of qualifications in philosophy, theology or natural science.”

Partisans of the work, however, have included poets Paul Valéry and W. H. Auden; it’s also worth noting that Charles Baudelaire translated it into French and Julio Cortázar into Spanish. More surprisingly, a consensus opinion has formed in recent decades around the notion that in its eccentric way Eureka anticipates key discoveries in astrophysics, such as the Big Bang theory and the concept of an expanding universe.

|

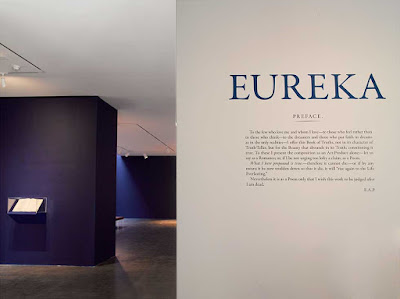

| Installation view of Eureka 508 West 25th Street, New York / May 1 – August 14, 2015 Photography by: Tom Barratt / Pace Gallery |

This is the side of Poe’s text that drives the ingeniously curated group exhibition at Pace, which is comprised of 23 works by 12 twentieth- and twenty-first-century artists. Successive artworks alternately portray objects in space—which may or may not be taken to represent planetary bodies—in two and three dimensions; a kind of visual echo or rhyme results from several of the show’s adroit juxtapositions. A 1934 mobile by Alexander Calder, for instance, bounces off an adjacent 1987 painting by Australian Aboriginal artist Yala Yala Gibbs Tjungurrayi, whose geometric shapes pulsate with a Keith Haring–like energy. James Turrell’s hologram of a full moon confronts viewers with a disorienting trompe l’oeil, while a nearby recording of Edgar Varèse compositions evokes, one might say, the music of the spheres.

|

| Installation view of Eureka 508 West 25th Street, New York / May 1 – August 14, 2015 Photography by: Tom Barratt / Pace Gallery |

As an incisive essay by Max Nelson on the Paris Review website summarizes: “the show is a delightful cabinet of curiosities that riffs playfully, if a little abstrusely, on Eureka’s atmosphere and tone.”

According to his biographer Kenneth Silverman, Poe intimated to a friend that his “prose poem” wouldn’t be properly appreciated until 2,000 years after its appearance. But from the evidence on display at Pace, it’s tempting to conclude that his prediction was off by about 1,800 years.

Eureka is on view at Pace Gallery New York City through August 28, 2015. Visit the Pace website for complete details.

Related posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment